Static Interface Members

C# 8.0 gave us default interface methods. They brought us, among other things, the way to introduce new API members without breaking current contracts. Interfaces however still lacked a ability to model “static” members out-of-the-box. Factories became our usual way of dealing with object creation but how about functionalities that class itself knows best how to handle. What about, say, parsing? Enter C# 11’s Static Interface Members (SIM)

Parsing

Let’s examine the following example:

public interface IMyParsable<TSelf>

where TSelf : IMyParsable<TSelf>?

{

static abstract TSelf Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider);

}

First that strikes to mind is “what do we need such generic guard here?”. Read more on Curiously Recurring Generic Pattern.

Rest of the example seems reasonable - this states that types implementing this interface must also contain static Parse method. This method can be used inside interface itself:

public interface IMyParsable<TSelf>

where TSelf : IMyParsable<TSelf>?

{

static abstract TSelf Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider); //provide implementation in implementing types

// this member does not seem to benefit much from being override-able

// so "virtual" modifier is omitted intentionally

static TSelf InvariantParse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s) =>

TSelf.Parse(s, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture);

//provide standard *Parse methods implementation

static virtual TSelf Parse(string s, IFormatProvider? provider) =>

TSelf.Parse(s.AsSpan(), provider);

static virtual bool TryParse([NotNullWhen(true)] string? s, IFormatProvider? provider,

[MaybeNullWhen(false)] out TSelf result)

{

result = default;

if (s == null) return false;

try

{

result = TSelf.Parse(s.AsSpan(), provider);

return true;

}

catch (Exception)

{

return false;

}

}

static virtual bool TryParse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider,

[MaybeNullWhen(false)] out TSelf result)

{

try

{

result = TSelf.Parse(s, provider);

return true;

}

catch (Exception)

{

result = default;

return false;

}

}

}

Let’s implement a simple class that will encapsulate notion of words that can be serialized in string separated with commas

record CommaSeparatedWords(IReadOnlyList<string> Words) : IMyParsable<CommaSeparatedWords>

{

public static CommaSeparatedWords Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider)

{

var words = new List<string>();

foreach (var word in s.Split(','))

words.Add(word.ToString());

return new(words);

}

public override string ToString() => string.Join(",", Words);

}

CommaSeparatedWords record will have other Parse and TryParse methods but calling them directly will not be possible i.e. CommaSeparatedWords.TryParse(...). So how can one effectively use them? Answer remains in generic guards.

static class MyParsableHelper

{

public static T ParseAs<T>(this string text, IFormatProvider? provider = null)

where T : IMyParsable<T>

=> T.Parse(text, provider);

}

//usage:

var words = "A,B,C".ParseAs<CommaSeparatedWords>();

But more probably this feature is more useful when wrapped in a class that delegates appropriate functionality. This class will parse line contents while delegating line parsing to CommaSeparatedWords:

record Lines<T>(IReadOnlyList<T> Values) : IMyParsable<Lines<T>>

where T : IMyParsable<T>

{

public static Lines<T> Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider = null)

{

var splitText = s.EnumerateLines();

var lines = new List<T>();

foreach (var line in splitText)

lines.Add(T.Parse(line, provider));

//this also works in this context

//var canParse = T.TryParse("", provider, out var result);

return new(lines);

}

public override string ToString() => string.Join(Environment.NewLine, Values);

}

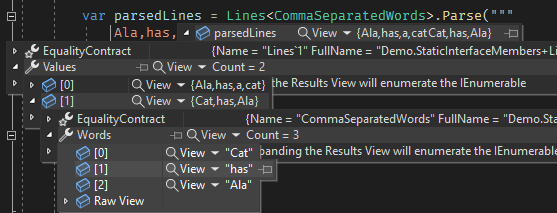

So the following code will properly parse

var parsedLines = Lines<CommaSeparatedWords>.Parse("""

Ala,has,a,cat

Cat,has,Ala

""");

as can be seen here:

Generic math operations

Let’s consider the following example

interface IAdditionOperation<T> where T : IAdditionOperation<T>

{

static abstract T Zero { get; }

static abstract T operator +(T lhs, T rhs);

}

record struct IntWrapper(int Value) : IAdditionOperation<IntWrapper>

{

public static IntWrapper Zero => new(0);

public static IntWrapper operator +(IntWrapper lhs, IntWrapper rhs) => new(lhs.Value + rhs.Value);

}

//we can now write universal "sum" method for all IAdditionOperation<T>

static T Sum<T>(IEnumerable<T> numbers) where T : IAdditionOperation<T>

{

var sum = T.Zero;

foreach (var number in numbers)

sum += number;

return sum;

//or:

//return numbers.Aggregate(T.Zero, (acc, current) => acc + current);

}

//which can be used:

var sum = Sum(Enumerable.Range(1, 10).Select(i => new IntWrapper(i)));

We could easily create other number wrappers now (for float, long etc.) but that would be pointless. While this example is great for demonstration, one could argue that, in order for it to work, such generic interfaces should be built into .NET number type system. They are. In next post we will explore these concepts.

Static polymorphism

Distinction between shadowed and “new” overrides for instance members existed in C# practically since it’s inception. Let’s examine how it’s defined for static members

interface IValues

{

static abstract string Static { get; }

string Instance { get; }

}

class Base : IValues

{

public static string Static => "Base";

public string Instance => "Base";

}

//this class shadows members

class ShadowImpl : Base, IValues

{

public static string Static => "Shadow";

public string Instance => "Shadow";

}

//this class defines "new" overrides

class NewImpl : Base, IValues

{

public static new string Static => "New";

public new string Instance => "New";

}

//we can now use generic method to print values

static void Print<T>(T t) where T : IValues

=> Console.WriteLine("{0,6}, {1,6}", T.Static, t.Instance);

//and these are our results

var @base = new Base();

var shadow = new ShadowImpl();

var @new = new NewImpl();

Base shadowAsBase = shadow;

Base newAsBase = @new;

Print(@base); // Base, Base

Print(shadow); // Shadow, Shadow

Print(@new); // New, New

Print(shadowAsBase);// Base, Shadow

Print(newAsBase); // Base, New

So these examples show that we have static polymorphism in C# now 💖. Whether you need that it’s up to you but I wonder when such concepts will find their ways into job interviews 😀

SIM in standard library

Parsing

One can assume that parsing is such important feature that appropriate interface should exist in standard library. It does, in 2 flavours in fact:

with later obviously extending the former. One can check, but most, if not all (with notable exception of bool), common types like int, float, byte already implement both of these interfaces.

This in turn allows us to use them a generic guards to implement a CSV parser for lines with 3 constituents and a class that will store/parse whole CSV file:

readonly record struct CsvLine<T1, T2, T3>(T1 Item1, T2 Item2, T3 Item3)

: ISpanParsable<CsvLine<T1, T2, T3>>

where T1 : ISpanParsable<T1>

where T2 : ISpanParsable<T2>

where T3 : ISpanParsable<T3>

{

public static CsvLine<T1, T2, T3> Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider = null)

{

// For some reasons ReadOnlySpan<char> does not possess a string.Split() equivalent.

// This example uses the SpanSplit approach from:

// https://www.nuget.org/packages/Nemesis.TextParsers/

var enumerator = s.Split(',').GetEnumerator();

if (!enumerator.MoveNext()) throw new("No element at 1st position");

var t1 = T1.Parse(enumerator.Current, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture);

if (!enumerator.MoveNext()) throw new("No element at 2nd position");

var t2 = T2.Parse(enumerator.Current, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture);

if (!enumerator.MoveNext()) throw new("No element at 3rd position");

var t3 = T3.Parse(enumerator.Current, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture);

return new(t1, t2, t3);

}

//remaining Parse methods omitted for brevity

}

record CsvFile<T>(IReadOnlyList<T> Lines) : ISpanParsable<CsvFile<T>>

where T : ISpanParsable<T>

{

public static CsvFile<T> Parse(ReadOnlySpan<char> s, IFormatProvider? provider = null)

{

var splitText = s.EnumerateLines();

var lines = new List<T>();

foreach (var line in splitText)

lines.Add(T.Parse(line, provider));

return new(lines);

}

//remaining Parse methods omitted for brevity

}

This will allow parsing to be done in following fashion:

var parsedNumbers = CsvFile<int>.Parse("""

11

22

33

""");

//or more advanced example

var parsedStructs = CsvFile<CsvLine<int, float, char>>.Parse("""

11,1.1,A

22,2.2,B

33,3.3,C

""");

Generic math operation

This topic is quite comprehensive. Stay tuned for a separate blog post. It’s scheduled for 5th of December 2022. We will attempt to implement whole generic type using new constructs